(… continued from The kernel of meaning in property rights)

RECAP: We said that for a rights structure to be efficient (i.e. for it to allow stuff to pass to those who value the stuff most regardless of the initial rights structure), it should be independent of agents’ actions. So e.g. it’s efficient to say “the thief owns a car from you” (so that you will owe a car to him even if you don’t make/buy one — you have to figure out a way to get one and give it to him), but it’s not efficient to say “the thief owns whatever number of cars you make”.

So “Might Makes Right” isn’t generally an efficient rights structure — because in MMR, the thief gets to steal the car you make, but doesn’t quite have the capacity to force you to make the car; so you end up not making the car, and GDP is reduced.

But you can hack this: you could introduce a new good into the economy (call this expanded economy Economy+1), called the “right to take your stuff”, and say the thief possesses that. Then it becomes a tradeable good, which you can buy from the thief at an appropriate price. Since you will produce more stuff if you possess the “right to take stuff from you” than if the thief does, the right is more valuable in your hands, so you are able to pay for it.

Oh! But it’s Might Makes Right, so the thief also possesses “the right to take the right to take your stuff”. Any economy in which the thief only possesses up to some computable ordinal of recursive rights is an efficient economy, but in Might Makes Right, the thief possess all the way up to \(\omega_{CK}\), which is not ok.

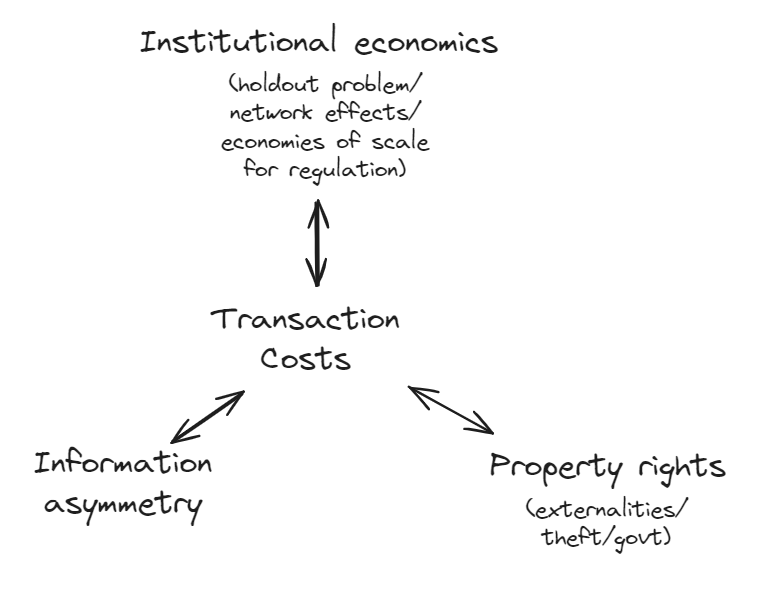

Observe the close correspondence between property rights and transaction costs. Buying “the right to take your stuff” from the thief had a transaction cost — which is exactly the cost of “the right to take the right to take your stuff”. So what was a transaction cost in Economy+1 is just a regular input cost in Economy+2 — you need “the right to take the right to take your stuff” in order to (effectively) get a “the right to take your stuff”.

I’m sure this all has some very nice interpretation in terms of thermodynamics, with transaction costs as heat, and that heat can get counted as work depending on your precise definition on the system, etc. I haven’t thought this through, but probably this work by Ortega & Braun (2012) is relevant: Thermodynamics as a theory of decision-making with information processing costs.

Suppose there are \(n\) goods in an economy, whose

The point worth making is that these four market failures are basically the same thing:

Some examples to illustrate the point—

Theft.

Regulations.

Gun control.

Language.

Pollution.

Information markets.