Total utilitarianism is fine

Take some agents \(A_i\) with utility functions \(U_i(x_1, ... x_N)\). In general if they are individually maximizing their utility functions, then their chosen actions \((x_1^*,\dots x_N^*)\) might be some Nash equilibrium of the game—but it may not be possible to interpret this as the action of a “super-agent”.

There are two ways to interpret the words “the action of a super-agent”:

As the action that maximizes some “total utility function”, where this total utility function has some sensible properties—say, a linear sum (with positive weights) of agent utilities.

If the two agents could co-ordinate and choose their action, there is no other action that would be better for both of them—i.e. is Pareto-optimal.

(a) is always (b): if \(\sum w_iU_i\) is maximized, then it is not possible for some \(U_j\) to be increased without decreasing the other $Ui$s; as that would increase the sum too.

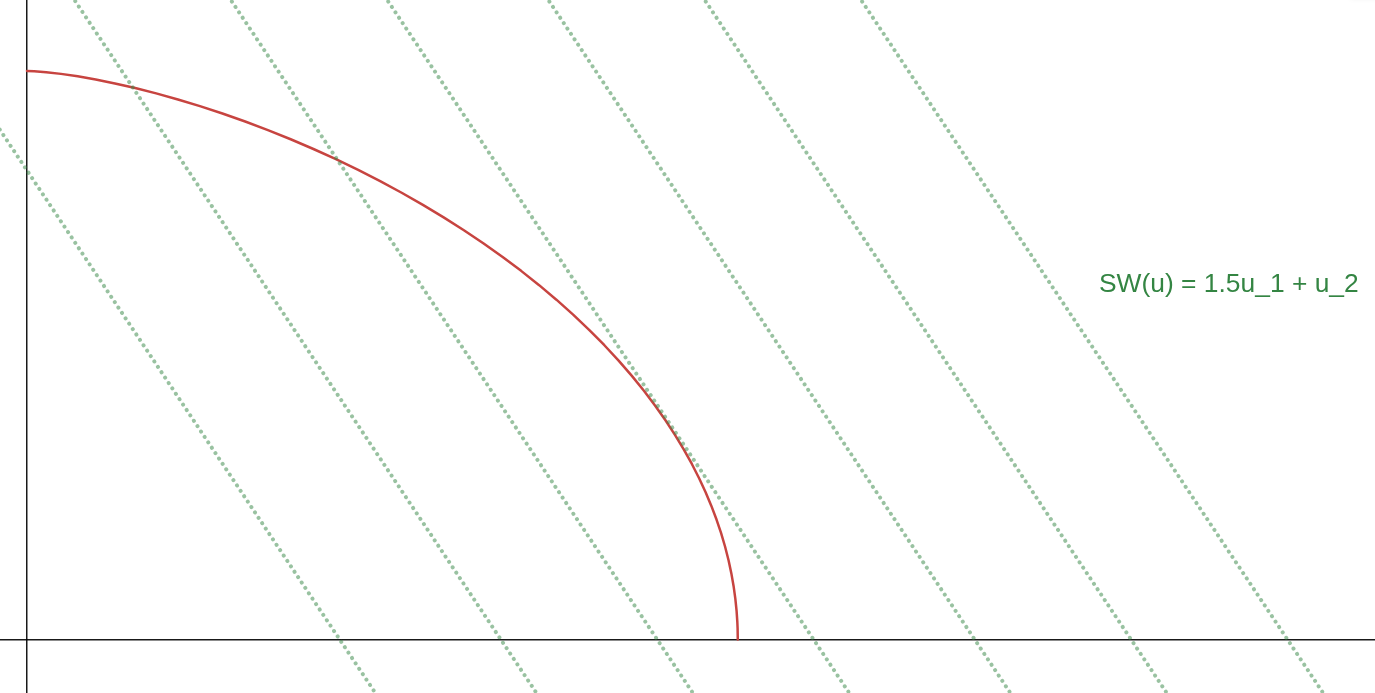

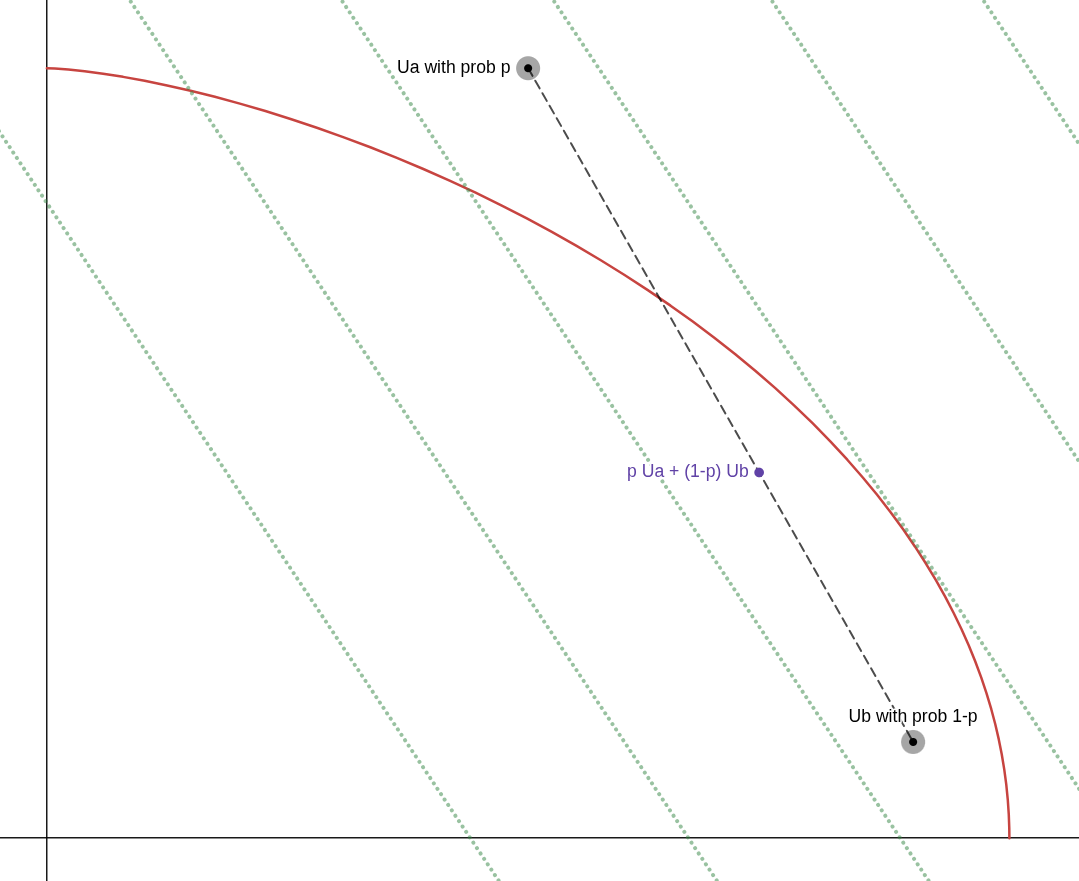

What about the converse? Is every Pareto-optimal outcome the argmax of some linear-sum social welfare function? Take the “Utility Possibility Frontier” of the agents (i.e. for every possible \((U_{-i})\) plot the maximum \(U_i\))—these are precisely the utilities of Pareto-optimal points. In utility space, a “linear sum of utilities” is a function with flat plane contours.

The point where the social welfare function’s contours brush the frontier is its optimal value. Certainly as long as the Pareto frontier is convex, there will be exactly one tangent line to every Pareto-optimal point and thus a unique “linear sum” social welfare function that it maximizes.

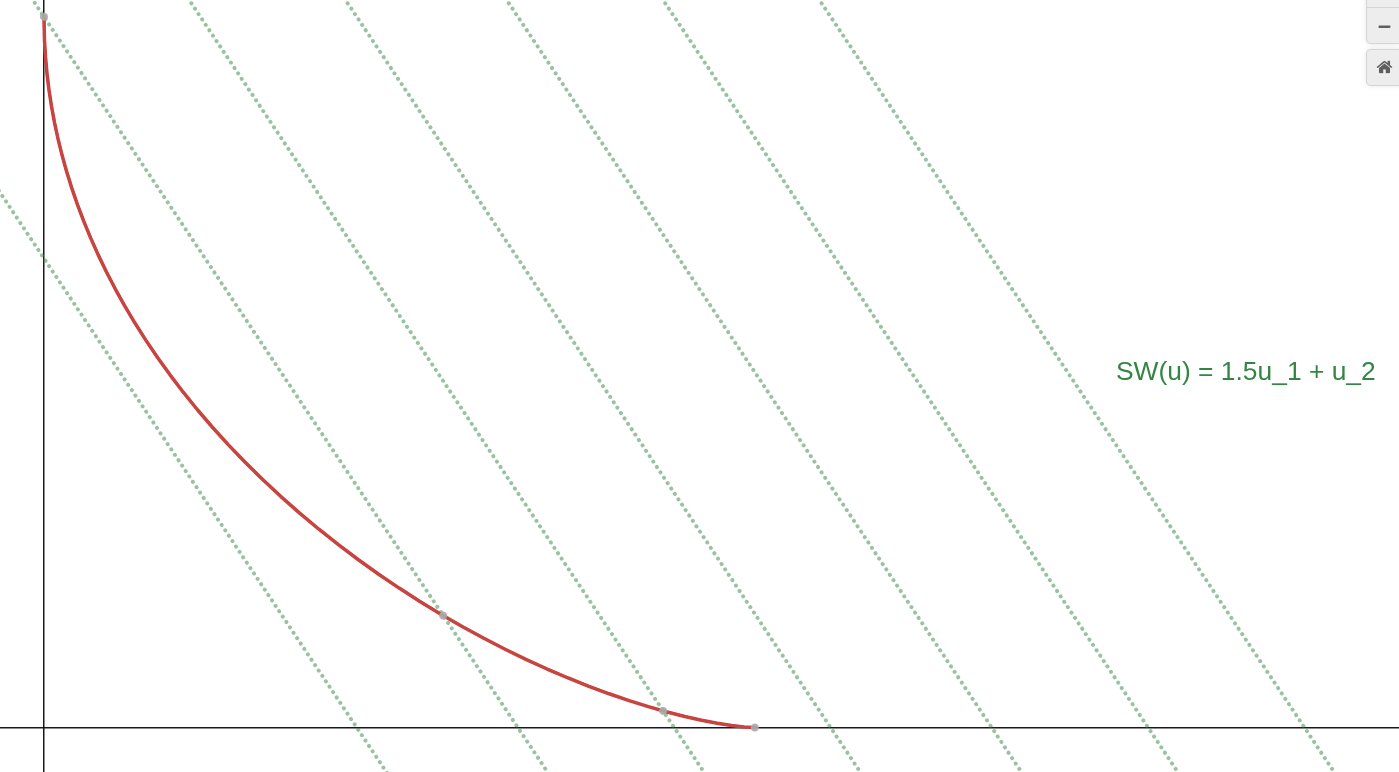

This is not the case when the Pareto frontier is non-convex: the points on the interior of this frontier (in the “dip”) are not the maximum of any linear-sum social welfare function, since the contours intersect the frontier well above it. This refers to a case where e.g. the utilities are \(U_1(x)=x_1^2\) and \(U_2(x)=x_2^2\) (where \(x_1+x_2=1\)).

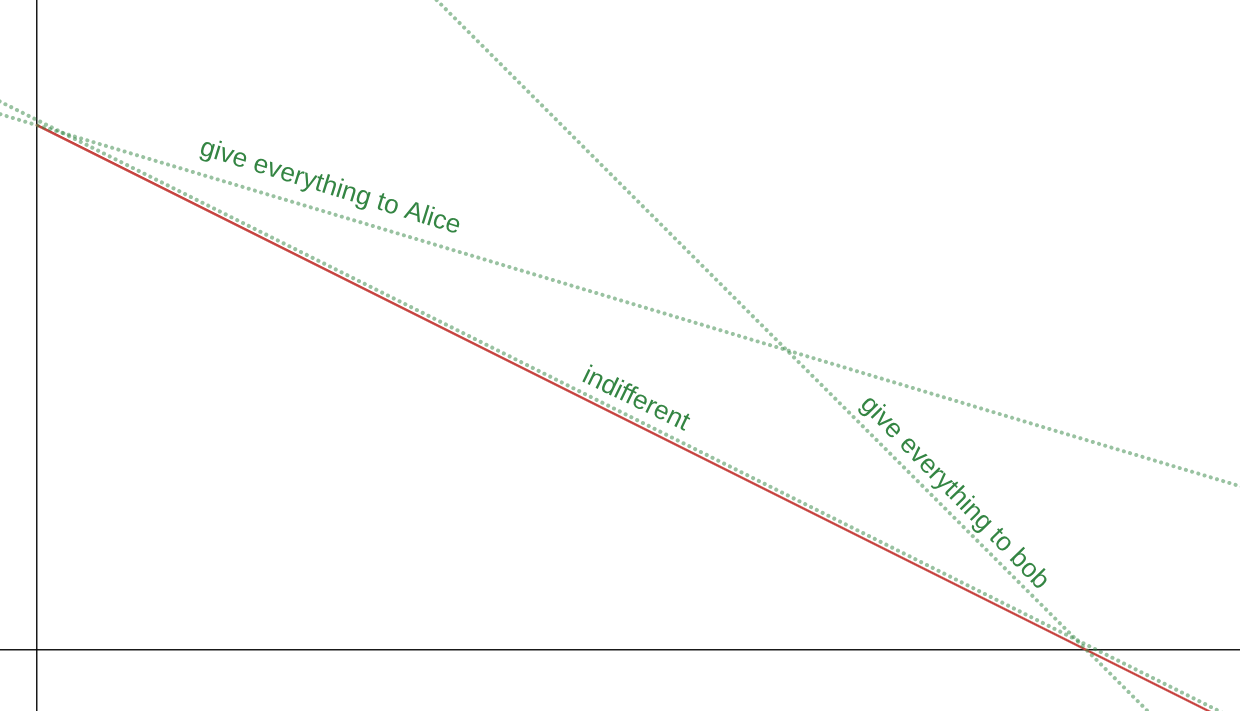

This explains the “equality” criticism of total utilitarianism commonly cited in social choice theory etc: i.e. “if Alice values a good at 1 utils/kg and Bob values it at 2 utils/kg, total utilitarianism can only tell you ”give everything to Alice“, ”give everything to Bob“ or ”do whatever IDC".

Well, I think this criticism is quite silly: it cites our intuition about real-world problems—where Alice and Bob would have diminishing utilities thus the utility frontier would be convex—to make an argument over an idealized world where this is not so. “But Alice and Bob favor a fair outcome!” — in that case you simply specified their utility function wrong.

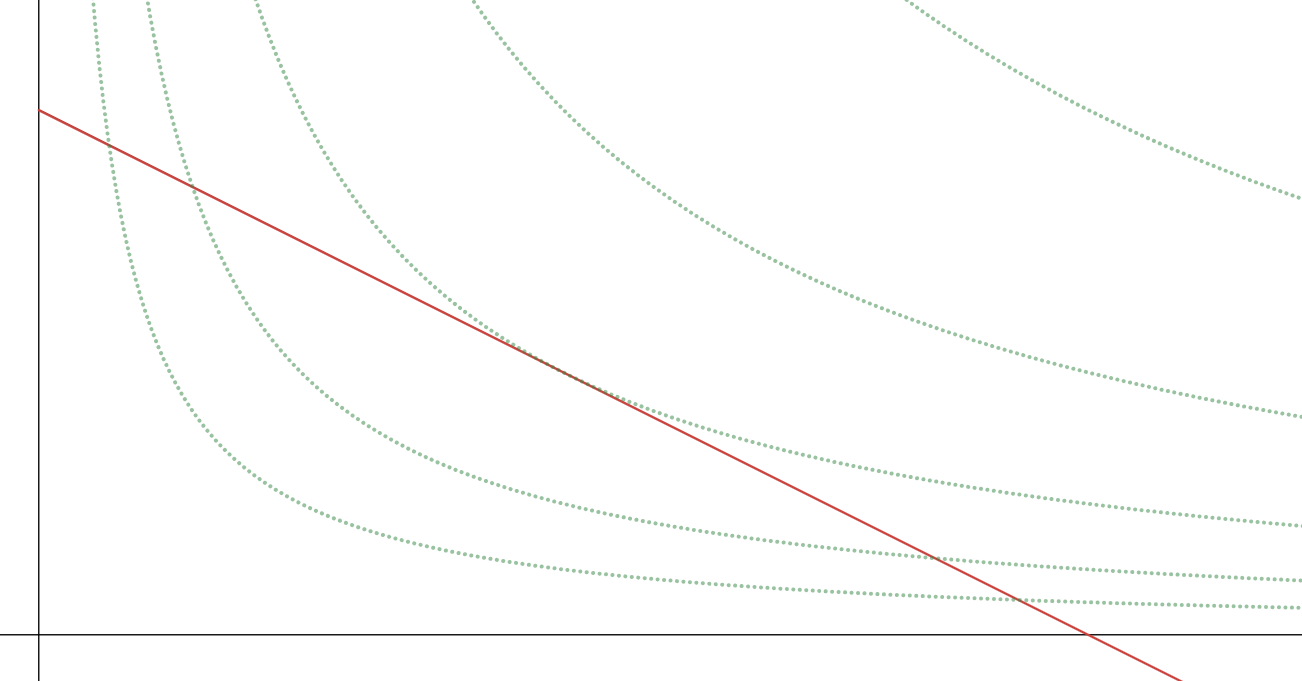

Still, we could say that Pareto optimality is more fundamental than linear-sum social welfare functions. For example, you could choose any point on a linear frontier with geometric social welfare functions:

In general, to build agents that may prefer any Pareto-optimal point, you need a social welfare function that is “more non-convex” in the utility functions (that has greater curvature) than the Utility Possibility Frontier. Linear sums are more non-convex than convex shapes; Geometric means are more non-convex than linear shapes, and the Rawlsian maximin (an L-shape) is the most non-convex of all (any Pareto optimum may be realized as the maximum of a suitably-weighted Rawlsian maximin).

Note that we have not actually yet touched Harsanyi’s aggregation theorem: we only showed that Pareto-optimal outcomes can be realized by the maximization of linear-sum social welfare functions, not that they must be. For this, Harsanyi adds one more assumption:

Pareto indifference: If every individual is indifferent between Lottery A and Lottery B, their aggregation must also be indifferent.

In other words: in utility space, the social welfare function at the purple point \(SW(p(u_{1a},u_{2a})+(1-p)(u_{1b},u_{2b}))\) must be equal to the linear sum of the social welfare function at those two points: \(pSW(u_{1a},u_{2a})+(1-p)SW(u_{1b},u_{2b})\). It is easy to see why this is is only satisfied by linear-sum social welfare functions.

This condition essentially says: not only should the super-agent aggregate the agents’ utility functions, it should also aggregate their risk aversion levels (rather than introducing its own, as geometric or maximin social welfare functions do). An expected-utility maximizer has its risk aversion integrated into its utility function (so it always maximizes expected utility, rather than some risk-adjusted version of it): if you believe that the agent should instead maximize the expectation of \(\log(U)\) or whatever, that just means you have used \(\log(U)\) as the utility function.

This axiom is the repudiation of the “veil of ignorance”, i.e. the argument “But what if Charlie is choosing whether to be born as Alice or Bob—he would prefer an egalitarian outcome, because he’s risk-averse!” Here, Charlie basically is the super-agent choosing for both Alice or Bob: if he is not going to be so risk-averse either as Alice or as Bob, he has no business being more risk-averse while he is an unborn child. We are only allowed to prefer equality to the extent that Alice or Bob prefer certainty—to be “geometrically rational” in terms of inequality if Alice and Bob are “geometrically rational” in terms of risk (i.e. if their actual, EUM, utility functions are actually the log of the utility functions they’re being “geometrically rational” with).

The basic point these criticisms of linear-sum social welfare functions miss is that the form of these utility functions is a statement about risk-aversion. What is the difference between a concave utility function \(U(x)=\sqrt{x}\), a linear utility function \(U(x)=x\) and a convex utility function \(U(x)=x^2\)? In a deterministic world, nothing: the preferences are the same \(1>0.5>0\). In a probabilistic world, it means the agents are risk-loving—they prefer the 25% chance of getting 1 unit as much as a 100% chance of getting 1/2 units. If you assume in your example that the agents have convex or linear utility functions (rather than concave), you assume that they disagree with your egalitarianism: they don’t want your safe solution where they’re guaranteed 0.5 instead of having a shot at 1 after going through the veil of ignorance. They want you to stop enforcing your communist beliefs on them. The “expected” in Expected Utility Maximization matters to the definition of utility!

This is why the whole “geometric rationality” stuff seems pretty much like another “Tau manifesto” to me: sure, maybe some things would get slightly neater if we said all our utility functions were actually \(\log(U)\), so that \(U\) could just be money or whatever—but nothing actually changes.