The Hamiltonian and exactly where it comes from

Constrained optimization

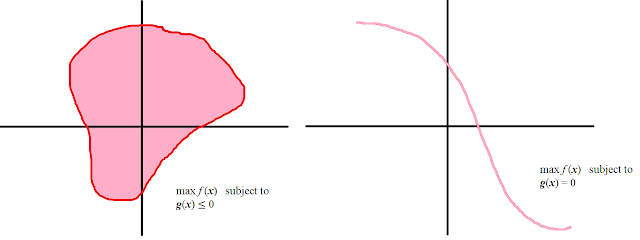

Suppose you wanted to optimize a function subject to some constraints (i.e. on a subset of \(\mathbb{R}^n\)) – so on something like the pink domains below:

If the optimal point \(x^*\) lies within the interior of a domain like \(g(x)\le0\), then we have the gradient \(f'(x^*)=0\) as usual – however, if the point lies on the boundary, then we could still be able to increase \(f\) by going outside the boundary, and still call \(x^*\) an optimal point, as such points lie outside the domain. But we must have that \(f'(x)\) must point precisely outward normal from the boundary, otherwise we can find a directional derivative within the region to increase \(f\) in.

So we have \(f'(x)=\lambda g'(x)\) for some \(\lambda\ge 0\) (with equality if – but not only if – \(x\) lies in the interior). And we also have the reverse implication if \(f\) and \(g\) are convex (why do they need convexity?). For equality constraints, we have the same constraint but don’t need \(\lambda\ge 0\) (why?).

But this is equivalent to optimizing the function \(f(x)-\lambda g(x)\) – for some \(\lambda\).

This function \(L(x,\lambda)\) is called the Lagrangian.

Duality