Table of Contents

I believe that we can build AGI as “markets of simpler programs”. In particular we should, because markets are an example of real-life Aligned Superintelligence, and they serve as a source for intuition-pumping for alignment.

Contents / summary:

- Analogies between markets and agents

- Cool features of markets

- Variable depth

- Generalization and Continual Learning

- Meta-learning and derived demand

- Bounded rationality and pagerank

- What are markets? The math

- Markets and backprop

- Related work

- Outlook and call for collaborators

1. Analogies between markets and agents

- Markets and agents do the “same kinds of things” (i.e. have the same “type signature”): they compute decisions (in the form of goods allocation) and beliefs (via e.g. prediction markets).

- Beliefs may be inconsistent (arbitrage) or incomplete. In fact, they must be incomplete, due to a simple counting argument.

- “Rationality” and “Efficient Market Hypothesis”. Both markets and boundedly rational agents are only “rational given the available algorithmic information”[1].

- Markets have self-awareness: they can contain prediction markets for the market’s own properties (e.g. “the market probability of XX prediction market will be >0.7“)1 and also can self-improve, because the algorithmic functionality of markets are also provided by some goods (e.g. “the labour supply of arbitrageurs”) and this supply can be adjusted and optimized.

- Abstraction is like economies of scale.

- Transaction costs are like computational costs.

- Markets are general intelligence: they can be asked (paid) to accomplish any task. In particular, they are intelligent about managing this generality: about forming abstractions (factor goods) that will be useful for the distribution of tasks they expect to be asked to accomplish.

The basic point is that

- Markets are boundedly rational agents

- You can actually get intelligence as an emergent property of markets (rather than the intelligence being just from the intelligence of the individual participants in the market). So you could imagine just building a market out of really “dumb” / simple programs, and the resulting market would be an intelligent agent.

The first point is clearly true; the latter could be more controversial. But (1) the idea of a multi-agent basis of mind/intelligence is not original to me, and has precedent in the literature — see “Related work” for details (2) this is intuitively very plausible, right? Think e.g. the “I, Pencil” essay: no human is intelligent / capable enough to single-handedly produce a pencil, yet the market distributes this highly complex task amongst many dumb humans. Specifically, markets achieve this level of distributedness via two methods:

- Modularity of action — instead of a single agent that completes the entire task \(\alpha:\Omega\to\Omega\), this action is decomposed into many smaller tasks \(\Omega\xrightarrow{\alpha_1}\Omega\xrightarrow{\alpha_2}\dots\xrightarrow{\alpha_n}\Omega\), with each little step optimized separately (by selecting the best agent for the subtask).

- Modularity of state — instead of handing the entire state \(\omega\) to an agent to transform it, we factor the state into dimensions called “goods”: \(\Omega=\Omega_1\times\dots\Omega_m\). See “What are markets? The math” for details.

2. Cool features of markets

Markets serve as an example of “already-existing (aligned) AGI”, so they serve as a nice setting for us to play with concepts of intelligence and alignment.

So even if we don’t want to build market-based agents, markets serve as a valuable intuition pump for the AI agents we do build.

Some interesting properties of markets / concepts of intelligence in the context of markets —

2.1. Variable scale

One thing bad about neural networks is that they have “fixed depth”. ChatGPT finds the prompts “Complete this sentence: Eenie Meenie Minie Moe, Catch the …” and “Debug this fairly complex piece of code” to be equally hard / takes equal number of computational steps.

I imagine this means that increasingly complex tasks just require more and more scale, and thus impractical amounts of resources.

(Note: this doesn’t mean LLMs are safe, because at some amount of scale the LLM can just become smart enough to build a more powerful AI framework, like marketic agents, or something like marketic agents but bad.)

Markets, by contrast, do not necessarily have a fixed structure. In the simplest example of a market (see “What are markets? The math”), you just have “the state of the world” getting auctioned to successive agents, which add value to it in some way. Depending on this initial state, the number of steps it goes through before being bought by the consumer (i.e. earning reward), and the computational cost at each step (the wage paid to the agent) could be completely different.

There is no upper bound on the scale / no “number of parameters” as such, because markets kinda do their own hyperparameter-optimization dynamically as we will discuss shortly.

You can get variable scale with LLMs by patching them together into an agentic workflow, but there’s no “optimization” on this like structure like there is within the LLM.

2.2. Generalization and Continual Learning

I’m going to say a weird thing: out-of-distribution generalization is a form of within-distribution generalization. — but a type of generalization that gradient descent is not very good at.

What does this mean?

Suppose you expose a learning algorithm to a stream of “varying” training data. Then ideally it should learn the variation in the training data and learn to be “adaptable” to the sort of variation present. Evolutionary algorithms do this to an extent: humans evolved to be adaptable, rather than overfit to every new twist of environmental fate, because the overfitting guys kept getting culled while the adaptable guys could pass all the tests.

Gradient descent doesn’t really do this: it is subject to catastrophic forgetting. If you optimize loss function \(L_1\), then optimize loss function \(L_2\), there is no sense in which you optimize the average loss function \(L_1+L_2\), or learn to check a few samples to check which environment we’re in, or anything like that: it simply myopically follows the direction given by the current gradient.

(Well, actually you can do this if you’re optimizing each loss function for like 1 step or a few — i.e. SGD — because you haven’t gone too far yet so the gradients live in the same tangent space. But the point is that gradient descent cannot learn “global” or “long-term” trends in the data stream.)

Markets, I think, are capable of continual learning, at least as long as you don’t let monopolies form. ### Meta-learning and derived demand

Let’s think about the Meta learning problem. Suppose \(P(X)\) is a task (distribution to learn). But in particular, the task \(P(X)\) is itself sampled from some distribution \(\phi_{P(X)}\) — equivalently, \(P(X)\) really depends on some other random variable \(\theta\), i.e. is really a distribution \(P(X\mid\theta)\). Then the meta-learning goals are to learn \(P(X\mid\theta)\) and \(P(\theta)\).

Now suppose you’re a skyscraper builder. Building skyscrapers entails some task \(Q(X)\) (a value function on possible actions) — but this task depends on local circumstances, like earthquake frequency, soil type, and nimby infestation which may be represented by some other random variable \(\theta\). The builder must learn \(Q(X\mid\theta)\), while \(P(\theta)\) is learned by providers of some information, or more generally you could say \(Q(\theta)\) is learned by producers of factor goods (including information).

Observe that the choice of such \(\theta\) is itself “learned”. The market not only learns, but also chooses what to learn. There is also no fundamental difference between meta-learning parameters and any other parameters that the market learns to learn.

In other words: stuff like hyperparameter optimization happens very “naturally” in markets, they simply appear as markets for factor goods.

2.3. Bounded rationality and pagerank

The current market probability for Trump winning the 2024 election is 60%.

Is this the rational probability? Well, if you took a perfect brain simulation of everyone who will vote in the 2024 election, you could probably come up with a much better estimate.

Instead, 60% is just the best we can do with the information — including algorithmic (e.g. logical) information — available. The fact that we choose not to take a perfect brain simulation etc. is another market decision — the market decision for “quantity of resources allocated to simulating voter brains”, which is low because we determined that “information on who will win this election” was not really worth that (impossibly high of a) cost.

But again, this market-calculated quantity is not perfect either — the price offered by the market for computational resources is, again, a price computed by a market of imperfect agents.

Similarly, the marketplaces / institutions that agents choose to trade on are also services that are chosen by agent demand, etc.

…

One reductive way to look at the problem of bounded rationality is that it’s just learning: that a boundedly rational agent is just a learning agent. See e.g. “asymptotic bounded optimality” in Bounded rationality and learning: a brief update. It’s ok that the agent isn’t optimal, as long as it eventually learns to be. It’s ok that the agent’s allocation of resources to this pursuit of optimality isn’t optimal, as long as it eventually learns to be. Ad infinitum.

Markets behave the same way: one agent’s reward mechanism is another agent’s behaviour, which is trained by its own reward mechanism, which is yet another agent’s behaviour, ad infinitum … and there are optimization pressures at each level.

2.4. Transaction costs and institutions

… DO NOT PVBLISH

3. What are markets? The math

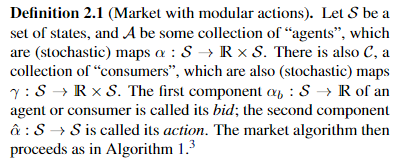

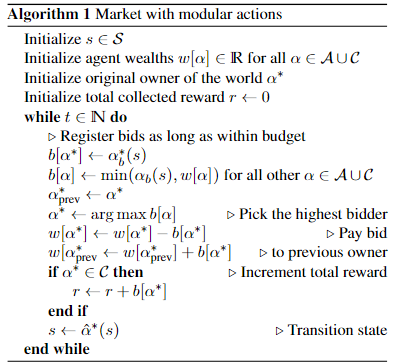

Some excerpts from a paper I have in progress. This “definition of a market” is valid in a setting that subsumes any MDP (proof left as an exercise), and subsumes the existing market-based RL toys listed in “Related work” (proof left as an exercise).

Observe that there is no fixed market graph or structure — this graph is generated/learned on the fly. The class of agents is not specified, and should be chosen so that a universal approximation theorem exists.

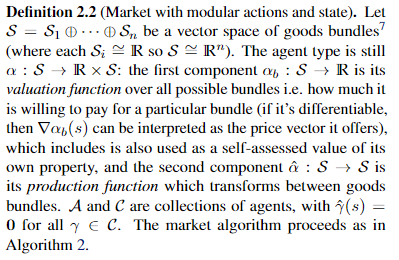

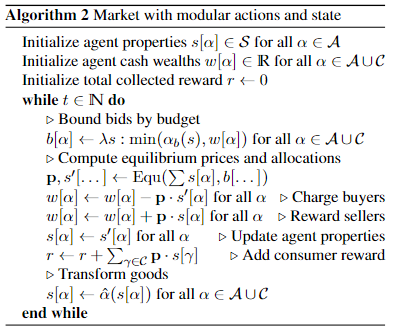

We may also consider markets where instead of transacting the entire “state” through the economy, the state is modularized into “goods” that are transacted separately. This way, agents can specialize not only on activation-conditions and actions, but also on what parts of the state to observe and act on.

(For neatness we’re pretending that there is some “general equilibrium computation algorithm” Equ — in reality you could imagine other mechanisms, e.g. asking for independent demand schedules for each good and computing their equilibria independently, so that the job of marginalizing their demand schedules on their estimated prices of other goods are left to the agents. You might generally have other mechanisms, requiring perhaps different signals from the agents, and it’s not clear to me exactly how to “abstract this out”. Perhaps the mechanism itself should be a good, IDK.)

3.1. Markets and backprop

What’s perhaps interesting with goods markets is that — although the market algorithm is not backpropagation, indeed the market does not even have a fixed structure to simply differentiate — at equilibrium, prices obey a certain chain rule relation.

i.e. if the agent can estimate what the market prices of its output goods will be (e.g. if prices are sufficiently stable to speak of a “prevailing price” \(\mathbf{p}\)), then it can simply compute its offered price via the chain rule. Where \(D\hat{\alpha}\) denotes the Jacobian of its production function:

\[\nabla\alpha_b=D\hat{\alpha}\cdot\mathbf{p}\] I guess this is the multivariable form of the claim made by John Wentworth in competitive markets as distributed backprop.

So prices are being backpropagated, and prices are derivatives (of benefit/cost). The offered price of steel being £1/kg tells you that there is £1 benefit to the world of increasing the production of steel by 1kg, the cost price of steel being £1/kg tells you there is £1 cost to the world of increasing the production of steel by 1kg; both of these are signals to change the production, albeit they cancel out.

BTW this means that at equilibrium \(\mathbf{p}\) is an eigenvector of \(D\hat{\alpha}\). I think this is a formalization of the “pagerank” connection I touched on earlier.

But key is that this backpropagation is not the only optimization the market does — it also simultaneously optimizes the whole market structure!

3.2. Multi-objective RL

DO NOT INCLUDE try to work out what markets look like with multi-objective RL

4. Intuition-pumping for alignment

DO NOT INCLUDE

Markets are a real-life ASI. What does this mean?

…

they receive continuous signal—which avoids misgeneralization

corporations “know their place”

Much of this is based on the taxonomy in Distinguishing AI takeover scenarios

Corrigibility

Reward-hacking / wireheading

Goodhart’s law

Influence seeking behaviour

Paperclip maximizer

Inner misaligned paperclip maximizer

6. Outlook and call for collaborators

So market-based agents are a promising idea for AGI, and we should develop AGI in the form of marketic agents. There are at least three schticks missing in this line of argumentation:

- So why haven’t marketic agents approaches, like those in “related work”, been a revolution already?

- Goods are an important part of real-world markets; how do you actually get “goods” in a general RL context?

- Do we really know that marketic agents — say with human “consumers” as the model of human feedback instead of RLHF or whatever — are really safe? Yes, real-life markets do great things, but we can’t just reason by analogy.

I think the main obstacle for getting marketic agents to work is that information markets are inefficient. They’re subject to buyer’s inspection/imperfect information and positive externalities (that’s the issue with prediction markets — sure, you can just subsidise one market with your “price for information” — but how can agents subsidize “subsidiary markets” that will help them in their forecast on your market, without creating positive externalities for someone else?). The Baum paper noticed this too — that you can’t have agents communicate useful information to other agents, like “in this scenario, don’t do X”.

This problem needs solving. Perhaps with an information bazaar (LLMs can act like a ]], so they can just inspect the information, make a purchase decision, then forget the information), or perhaps with "[[https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/ufW5LvcwDuL6qjdBT/latent-variables-for-prediction-markets-motivation-technical][latent variable prediction markets". Maybe combinatorial prediction markets are a relevant concept — is anyone familiar enough with the literature to tell me if they can do latent variable discovery?

A good starting to-do for this project will look something like this:

[ ]Write a Python module for working with generic marketic agents experiments. Stuff like the classifier systems papers should be easily reproducible as example runs.[ ]Figure out where goods come from. I think the answer has to do with the “actions” in the RL tuple, assigning rights to them and contracts over those rights.[ ]Write a LessWrong post titled “Intuition pumping for alignment” exploring what common alignment failure modes would look like with markets, and why they do not show up with markets (or if they do, how we can prevent them — I suspect this will be a lot easier with markets than with other AI models — something like “land value tax + antitrust” would do it).[ ]Make some basic theoretical connections like:[ ]How markets can subsume a POMDP setting — perhaps this will also shed light on questions about information, and about different market mechanisms which involve eliciting different signals from agents.[ ]The Reward Hypothesis is false is a nice reading on multi-objective MDPs, btw.[ ]Explain what a universal approximation theorem would look like, and some kind of optimality theorem though it’s unclear how to choose a natural “discount factor” (interest rate).

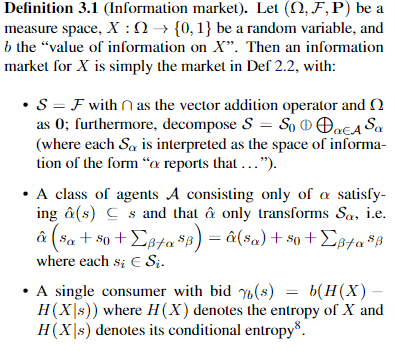

[ ]Solve the information market issue[ ]Explore information bazaar. It’s a novel idea with a lot of un-explored applications IMO. It can be applied to prediction markets subsidizing subsidiaries, to RLHF alternatives, to recommender systems, etc.[ ]Explore latent variable prediction markets.[ ]Think about whether the below definition of information markets makes any sense.

This will be a big project — I’m literally demanding that all AI work everywhere be reoriented towards marketic agents, and the TO-DO above is the bare minimum I need to do to produce valuable results to even convince anyone marketic agents is even a worthwhile research area.

If you think this is something you can meaningfully work on (if reading this post “struck a chord”, with related thoughts you’ve had before, if you have an economist’s intuitions), please reach out.

This project will be the greatest human achievement since the invention of agriculture. If we succeed, we will solve not only AI alignment, but also basically all of economics as well as philosophy.

Footnotes:

This also means markets are subject to Gödelian incompleteness: the market cannot correctly price, at time t, the asset “this market will have market probability <0.4 at time t”.